The Franco-German-Spanish Future Combat Air System, better known as FCAS, now faces its toughest moment. France has told Germany it wants about 80 percent of the work on the new fighter that anchors the program. The number surfaced late Sunday and was confirmed by people close to the talks. If Paris holds that line, the current parity deal dies and Berlin’s stake shrinks to a token slice. Spanish industry would lose almost as much. Negotiators ended the weekend without setting a fresh meeting date.

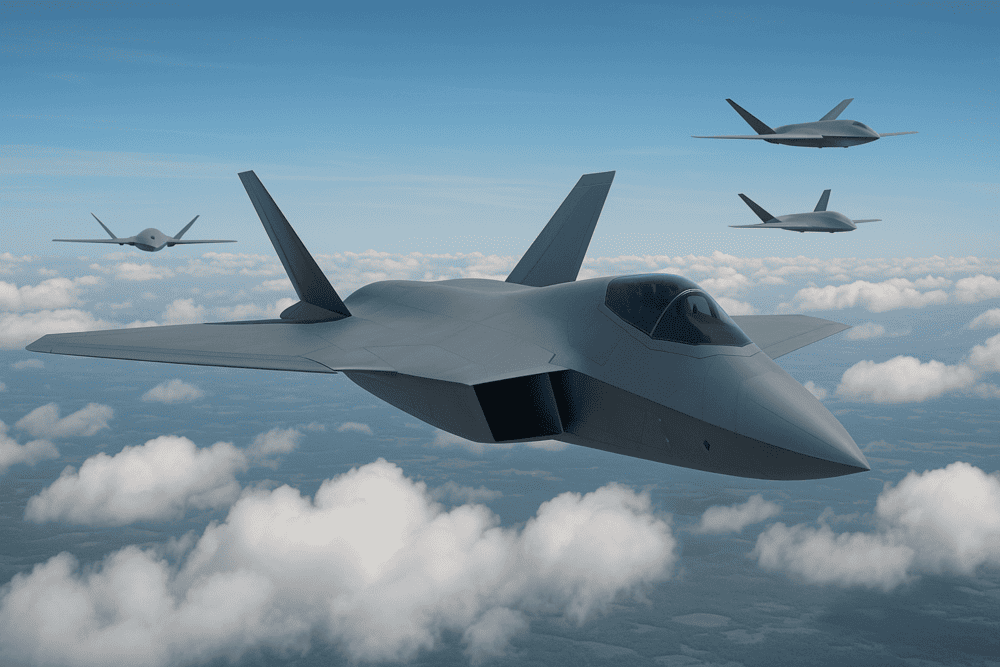

FCAS is Europe’s flagship air-power project. Launched in 2017, it ties a sixth-generation fighter, unmanned wingmen, a combat cloud, a new engine, and advanced sensors into one system. The program is priced at more than €100 billion and is supposed to field an operational jet by 1502040. Until now, work had been shared in rough thirds among Dassault of France, Airbus sites in Germany and Spain, and dozens of suppliers spread across the three nations.

According to industry sources, the new French demand reached the German defence ministry late Friday. It asks for design leadership on the fighter, the core avionics, and the main flight-control software – everything that defines the airframe. Berlin officials replied that the 2022 framework remains the only binding text. Madrid passed the notice to Indra, its prime contractor, but said nothing in public.

Defense officials in Berlin confirm that the ministry sees the request as a breach of trust, not a minor realignment. Christoph Schmid, the Social Democratic Party’s rapporteur on FCAS, called it a potential “last nail in the coffin.” He warned that German money cannot fund what amounts to a French national project. Airbus management echoed the concern but kept its language guarded, noting only that all partners must “respect earlier parameters.” A union meeting at Airbus Defence & Space in Manching opened this morning to brief staff on possible fallout.

German industry feels the hit first. Hensoldt, MTU Aero Engines, and dozens of medium-sized electronics houses depend on FCAS research grants already filed for 2025-2027. Roughly 7,800 skilled jobs ride on the program, a figure taken from the German Aerospace Industries Association’s latest audit. Works councils fear that the 80 percent claim would bleed those positions into France along with the high-value intellectual property.

Why push now? Dassault chief executive Éric Trappier hinted at the move during last month’s Paris Air Show, stating that his company could build a new fighter alone. Paris backs him because design control secures export leverage and long-term maintenance income. In simple terms, the state that holds the digital backbone owns the jet.

Spain finds itself caught in the middle. Indra handles the sensor suite and parts of the combat cloud, but those tasks shrink if France assumes the architectural lead. Spanish officials, who spoke under condition of anonymity, say they will resist any change that moves intellectual property out of Madrid. Yet they admit their leverage is weak without Berlin.

Three routes lie ahead:

- Renegotiation – Paris scales back the 80 percent target, settling near the original one-third split. Talks resume before the end-of-year deadline for Phase 2 contracts.

- Realignment – Germany and Spain quit FCAS and deepen ties with the UK-Italy-Japan Global Combat Air Programme (GCAP), accepting a 25 percent share there.

- Hybrid – A merger of FCAS and GCAP, floated by think-tanks, creates a single European-Japanese track and dilutes any one nation’s dominance.

The timing could not be worse. Phase 2, which covers flight-worthy demonstrators, was slated to start this autumn. Delays push risk items – engine core tests, composite wing molds, and air-combat cloud trials – into 2026 or later. Each slip widens the gap with the U.S. Next-Generation Air Dominance timeline and the still-tentative Chinese sixth-gen path.

Financial pressure also mounts. France already shoulders about 42 percent of Phase 1B spending, Germany 33 percent, and Spain the rest. Paris argues that its higher cash share justifies more work. Berlin counters that workshare once linked to cash would let wealthier states muscle out smaller partners in future joint weapons.

Technology integration now hangs in balance. The main components include:

- Remote-carrier drones able to fire beyond-visual-range missiles.

- A secure combat cloud that links pilots to satellites and ground stations.

- A clean-sheet engine with adaptive cycles for long range and low observability.

- AI-driven cockpit aids that cut pilot workload in dense electronic warfare.

Pull any one of those out of Germany or Spain and the other two pillars, drone autonomy and cloud control, lose synergy. Engineers warn that writing separate interface standards after the fact is slower and costlier than doing it once at the center.

Inside Airbus, anxiety is real. Assembly lines for Eurofighter upgrades will taper off in the early 2030s. Without FCAS follow-on work, the Manching site risks downsizing well before the new jet arrives. Indra tells Spanish unions a similar story about its radar labs near Madrid. Dassault, meanwhile, keeps building Rafale until at least 2035 and can survive alone.

From a policy angle, the dispute tests Europe’s mantra of “strategic autonomy.” A split FCAS weakens the EU pillar of NATO and pushes Germany to shop elsewhere. Berlin officials already study a slot in GCAP, which promises equal sharing among three nations and quicker prototype goals.

The French side insists the 80 percent claim is a starting bid, not a line carved in stone. Diplomats say President Emmanuel Macron and Chancellor Boris Pistorius – representing the caretaker cabinet after the June elections – may speak by phone this week. No date is fixed, but aides hint at a combined appearance at the NATO summit later this month if progress emerges.

What happens next?

- Phase 2 contracts must be signed by 31 December to keep the 2040 in-service date credible.

- EU-funded technology calls linked to FCAS expire in March 2026; missing that window forfeits up to €1.8 billion in matching funds.

- German parliamentary approval of the 2026 defense budget, set for mid-September, needs a clear FCAS line item to pass the finance committee.

- Spain holds a general election in November, and any stalled program risks becoming campaign ammunition.

No single step kills FCAS outright, yet each delay erodes political cover. Investors read the signals. Airbus shares slid two percent on Monday, while Dassault edged up one percent on Paris expectations of greater control.

France may test an alternate ratio – industry chatter mentions 60 percent – at a staff-level meeting penciled in for late July. Berlin could entertain that figure if it gains engine intellectual-property rights, a long-running sore point. Spain wants written safeguards on radar and cloud data. None of those trades look simple, but they are easier than starting over.

The wider European defense scene also weighs in. Italy’s defense ministry has wooed German suppliers to GCAP since May. The UK describes its program as “open,” with governance rules already set. Tokyo, keen to keep timelines short, would accept German avionics packages if schedules align.

Phase 2 is more than paperwork. It funds a full-scale demonstrator, high-temperature composites for the engine nozzle, and at least two unmanned wingmen. Skipping any piece forces redesign later. Engineers call that the “Christmas-tree effect” – leave room for one extra ornament, end up rewiring the whole tree.

Today’s stand-off is stark but not final. Paris gains leverage by showing it can walk. Berlin counters by flashing the GCAP option. Madrid holds swing votes in both camps. Each side knows the cost of failure equals handing the edge to non-European suppliers for the next thirty years.

Negotiators have little time and less goodwill. Yet past Franco-German rows – on tanks, on missiles, even on the Airbus A400M – eventually found compromise. Whether that record holds again will decide if Europe fields a home-grown fighter in the mid-century sky or rents technology from abroad.

REFERENCE SOURCES

- https://au.finance.yahoo.com/news/france-wants-80-workshare-franco-135009204.html

- https://www.reuters.com/business/aerospace-defense/paris-demands-80-workshare-franco-german-fighter-jet-says-source-2025-07-07/

- https://www.hartpunkt.de/fcas-erhaelt-frankreich-80-prozent-am-neuen-new-generation-fighter/

- https://www.vogon.today/economic-scenarios/fcas-at-risk-france-aims-for-80-of-the-sixth-generation-fighter-germany-cheated/2025/07/07/

- https://www.airdatanews.com/france-establishes-80percent-stake-in-european-6th-generation-fighter-program-reports/