Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI) and Japan’s Acquisition, Technology and Logistics Agency (ATLA) have signalled a shift in Tokyo’s approach to defence exports. They’re offering to hand all intellectual property related to the Mogami-class frigate to Australia. This marks a departure from Japan’s decades-long policy of strictly domestic defence development, confined to the Japan Self-Defense Forces.

Industry sources confirm ATLA head Sayako Sumomo described MHI’s IP transfer plan as a potential blueprint for future Japanese arms exports. Officials say the move aims to show serious commitment at the highest levels, from the prime minister to economic and defence ministers.

Australia is evaluating the Mogami in its SEA 3000 General Purpose Frigate competition. The rival is Germany’s ThyssenKrupp Marine Systems offering the MEKO A-200.

Japan’s defence export policy has largely avoided major weapons sales since World War II. But Tokyo plans to publish a formal strategy by the end of 2025. That aligns with recent moves to boost defence-industry ties and expand military cooperation. The Mogami offer signals Tokyo is ready to back strategy with action.

Australia and Japan have been aligning naval cooperation. A Mogami-class frigate visited Darwin in June as part of a pitch to the Royal Australian Navy. Defence officials confirm the ship demonstrated its advanced combat systems, anti-submarine and mine-countermeasure suites, and a compact 90-person crew – factors which appeal to Canberra amid recruitment challenges.

Defence experts note IP transfer is a key differentiator. Euan Graham, a Japan-Indo-Pacific expert at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, told us that providing IP would “be a significant sign of further movement in Japan’s favor”. Peter Dean of the US Studies Centre echoed that from Australia, saying it “goes to show how serious Japan are and how this is a whole of defence (industry & government) effort”. He argues it positions Japan as a long-term strategic partner rather than a one-off seller.

According to MHI and ATLA, they hold confidence in their ability to transfer ship-building methods. Osamu Nishiwaki of ATLA stated they can share digital ship-building and process know-how with Australian yards. That could ease integration challenges for Canberra, where compatibility and supply-chain integration remain top priorities.

Australia’s decision will hinge on three key factors: delivery schedule, budget adherence, and integration risk. Jennifer Parker of the University of New South Wales notes integration of supplies and systems matters more than IP rights . Canberra needs the ships sooner rather than later, with surface combatant fleet dropping to nine vessels next year. A delay in fleet readiness could affect the outcome.

Japan has outlined a delivery commitment: the first Mogami frigate arriving by 2028, contingent on final award and schedule adherence. That aligns with Canberra’s “speed to capability” requirement highlighted by Euan Graham. He said that commitment constitutes a major advantag.

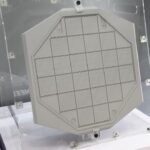

Japan is simultaneously modernising its own fleet. MHI launched the eleventh Mogami frigate, Tatsuta, in Nagasaki earlier this month. Upgrades include an expanded Mk 41 vertical launch silo, new sonar and radar systems. In May, Japan commissioned the seventh ship, JS Niyodo, with the Mk 41 VLS installed from the start. That progress highlights operational maturity now being matched with export intent.

ATLA signed two contracts with MHI on May 9 totalling roughly USD 1.03 billion – one for an improved Mogami variant and another for a replenishment vessel. These developments show the domestic programme is accelerating. MHI and ATLA are working to build 12 upgraded FFM vessels by 2033.

Tokyo also showcased its defence portfolios at exhibitions like DSEI Japan in May. Defence Minister Gen Nakatani framed it as evidence of Japan’s expanding overseas cooperation. That context makes the Mogami offer part of a larger export push.

This isn’t Japan’s first exploration of joint systems. It participates in the Global Combat Air Programme with the UK and Italy, targeting a sixth-generation fighter by 2035. That multilateral, weapon-design collaboration sets a precedent. Sharing IP via a frigate sales package could be Tokyo’s first major step in replicating that model for naval systems.

Observers agree that risks lie ahead. Tokyo lacks experience in building warships abroad. TKMS has exported to several navies, while Japan never has. A former Japanese ambassador, Shingo Yamagami, cautioned that Japan faces a learning curve in foreign certification and integration systems. The MQ is whether Japan can rapidly adapt to Australia’s regulatory and operational standards.

Financial terms also matter. Canberra expects a cost-effective deal, and IP transfer sometimes complicates pricing. Executives at TKMS argue their MEKO A-200 is a proven, low-risk choice. But Japan counters with shared design compatibility. Upgraded Mogami reportedly retains 85 % commonality with earlier models, which mitigates design risk.

Australia is set to announce its decision before the end of the year. If MHI wins, and IP is transferred, it could inaugurate a Japanese model for defence exports. That would reflect a strategic export doctrine with design control, long-term industrial ties, and fleet interoperability above short-term sales.

For Japan this would signal more than just a commercial win. It would mark its transformation into a global defence partner. MHI and ATLA aim to tie naval standards and ship-yard capabilities into local economies. That could set a template for future U.S., European, or Indo-Pacific partners seeking Japanese designs.

Delivering IP may also streamline lifecycle costs. Owning the blueprint means Australia could source upgrades or replicate systems without returning to Japan. It creates independence. MHI still expects ongoing collaboration. But Australia would hold the keys should needs shift over decades.

The Mogami programme also supports workforce readiness. Japan’s domestic plans call for two vessels built per year. Upgraded FFM output accelerates to twelve in five years. If Australia joins, that volume could fund continuous production, benefiting Japanese shipyards and ensuring economies of scale.

Our analysis shows Canberra will weigh that long-term industrial base against certification risks. But MHI’s track record, Japan’s recent production pace, and government backing lend weight. This isn’t a standalone bid. It’s a strategic offer: designed for co-development, co-production, and open architectural transfer.

In case of success, other export opportunities could follow. Indonesia once eyed Mogami frigates but chose other models. Renewed success in Australia may revive interest abroad. That could kickstart a broader maritime export path for Japan, aligning with Japan’s 2025 export strategy.

Tokyo’s approach fits into regional dynamics. Strengthened Japanese-Australian defence ties factor into Indo-Pacific security. Mogami’s design addresses shared maritime risks. And IP sharing reassures partners of Tokyo’s openness.

Australia seeks eleven general-purpose frigates from 2026 onward. If Canberra opts for Mogami, the first Japanese-built hull would hit Pacific waters in 2028, followed by local builds. That path resembles U.S. Foreign Military Sales in scale and intent. Japan may replicate that model.

If this mechanism spreads, it could reshape Japan’s role on the global market. It may allow easier sharing of future platforms, like the joint fighter from GCAP. IP transfer may turn from one-off exception to normal business practice.

The Mogami offer shows Japan’s new mindset. It blends strong domestic capacity with global cooperation. It offers future partners design mastery, industrial integration, and delivery certainty. That’s the model Tokyo hopes to replicate.

If the deal closes, expect other governments to take note. IP-inclusive defence sales could become Tokyo’s hallmark. And partners like Australia may benefit from long-term ship availability and independence.

That said, the follow-up will test whether Japan can deliver on contracts, support foreign shipyards, and respect partner needs. Canberra will likely look closely at Australia’s experience with U.S. or German systems. Japan now must prove it can compete in that landscape.

REFERENCE SOURCES

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_FFM

- https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2025/01/05/japan/politics/japan-defense-exports-strategy/

- https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2025/02/13/japan/japan-australia-mogami-drills/

- https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2025/07/japans-mhi-launches-eleventh-mogami-class-multirole-frigate-for-jmsdf/

- https://breakingdefense.com/2025/07/japans-mogami-offer-including-ip-rights-could-be-model-for-tokyos-future-exports/

- https://breakingdefense.com/2025/07/us-australia-and-japan-sign-trilateral-naval-logistics-agreement/

- https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/15833387

- https://www.reuters.com/world/china/japan-flexes-defence-ambitions-arms-show-2025-05-21/

- https://apnews.com/article/7b94ac7e0a2766ff2ddf32b0b8875596

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mogami-class_frigate

Launching_ceremony_2025-07-02-1.jpg)