Lockheed Martin’s F-35 program has drawn thousands of reader remarks on Aviation Week since the aircraft reached initial service. The most pointed thread this week grew out of a comment by retired Marine officer Don Bacon. He noted that “150 to 160 modifications” sit between many early-build jets and the Block 3F standard that the U.S. services need for combat. His remark sparked fresh debate about concurrency, spiraling costs, and schedule risk.

Program officials frame the 150-plus fixes as routine evolution, yet the list covers structural cracks, wiring chafes, fuel-system seals, and software faults. Each fix looks small by itself, but the total touches every major assembly. Engineers must open wings, drill out titanium panels, and run new fiber lines. Maintenance crews call the task a second final assembly line that will last for years.

Block 3F Software Stability and ALIS Challenges Impacting F-35 Operational Readiness

The Joint Program Office admits that bigger hurdles also remain. Block 3F software, the heart of the 2018 Initial Operational Test and Evaluation plan, still throws stability errors in mission-systems labs. Test pilots report sporadic radar resets and sensor fusion drops at high angles of attack. Until those quirks vanish, operational testers will not sign off on live-fire trials or confirm weapons envelopes.

ALIS, the Autonomic Logistics Information System, is another weak link. In June the Marines grounded an entire F-35B detachment at Yuma after a data-corruption glitch locked out maintenance functions. The patch arrived twelve days later but confidence fell again. Line chiefs now print paper forms as a back-up before every sortie.

The immediate schedule target is February 2018, when 23 “production-representative” aircraft must start full-up IOT&E. Readers point out that only a handful of jets actually meet that yardstick. The rest require tiger-team work at depot centers to swap out legacy parts. Program leaders admit that the test fleet may slip, yet press ahead in public statements.

Money shadows every deadline. The Pentagon’s pricing director launched a “deep dive” this summer to pin down what a fully corrected jet will cost. Analysts see two unknowns: first, the unit cost of the current lots built with known defects; second, the bill to retrofit more than 900 airframes already on the line. Early congressional budget worksheets give a wide range, but none include the cost of undiscovered flaws that the next test phase will reveal.

Concurrency and Retrofit Costs Burden Lockheed F-35 Production and Sustainment

Concurrency – building jets while still discovering faults – created the squeeze. Lockheed pushed out low-rate production blocks to keep factories warm. Customers wanted airplanes on ramps for training. The trade-off pulled tomorrow’s upgrade budget into today’s assembly halls. The result: hundreds of “prototype” aircraft now need rework while fresh ones continue to roll out in parallel with calls to boost F-35 production rates, despite fleet-wide issues.

A classified Pentagon estimate pegs the retrofit bill in the double-digit billions. Services must carve that sum out of procurement accounts that also fund new buys. The Joint Program Office asked Congress to raise the “cap” on modification funding, warning that, without relief, production lines could slow or even halt as workers and parts migrate to depot hangars.

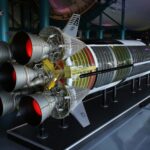

Key modification clusters

- Airframe: Wing-root rib reinforcement; bulkhead crack repairs; new coatings on tailhook springs.

- Propulsion: High-temperature turbine blades; cooling-air ducts sized for hotter Block 3F electronics.

- Avionics: Updated Fibre-Channel switches; refreshed processor cards; redesigned display units that no longer delaminate.

- Software blocks: 3F mission code; radar-fusion logic; secure datalink patches.

- Support systems: Fuel-tank vent redesign; lightning-protection layers; arresting-hook proximity sensors.

Each cluster touches different suppliers. Line managers juggle scarce parts among operational wings, depot centers, and the Fort Worth final assembly plant. A Navy maintainer notes that shipping shelves now look like “a Manhattan parking lot at rush hour.”

Strategic implications ripple outward. Allies such as Australia and Norway purchased early lots. Their airframes share the same fix list. Canberra’s defense ministry warns that schedule slippage could compress pilot conversion courses and delay squadron milestones. Oslo ordered extra spares in case the retrofit pipeline bottlenecks.

Challenges in F-35 Sustainment and International Partner Concerns Amid ALIS and Odin Program Issues

Meanwhile, rival programs watch. Boeing’s Block III Super Hornet upgrade package promises low risk and quick delivery. Although the Navy remains committed to the F-35C, several lawmakers cite the Hornet’s simpler upgrade path as leverage in budget hearings.

Even the schedule for the pivotal Milestone C full-rate production decision now looks shaky. Officially, April 2019 remains the goal. Unofficially, insiders expect that date to shift until every IOT&E gate closes and retrofit plans mature. Industry lobbying to lock in multiyear contracts continues, yet oversight committees want firmer performance evidence first.

Reader comments capture that frustration in plain language. One calls the program a “prototype parade on taxpayers’ dime.” Another objects to the term “Block 3” when so many fixes address basic flight safety. A third questions whether the program knows its true cost at all. Such candor, rarely matched in formal press releases, highlights how online forums shape public perception.

Still, not all voices criticize. Pilots praise the jet’s sensor reach and classified electronic-attack suite. A Marine captain on deployment credits the helmet-mounted display with spotting small boats hours before legacy jets. The rhetorical battle therefore pits operational highlights against systemic acquisition flaws. That tension feeds every comment string.

Lockheed F-35 Block 4 Development Amid Sustainment Costs and ALIS Readiness Challenges

Inside the Pentagon, planners work on the next leap, Block 4, even as Block 3F struggles toward closure. Block 4 adds new weapons racks, improved cockpit displays, and fresh computing architecture. Yet Block 4 depends on Technology Refresh 3 (TR-3) hardware that remains only a lab article today. Some engineers fear a “snake-eating-tail” cycle if TR-3 slips, dragging Block 4 and future weapon clearances with it.

International partners grow restless. Canada reopened its fighter competition. Turkey’s participation froze after diplomatic clashes. The United Kingdom still backs the jet but eyes sustainment costs that trend above prior estimates. U.S. officials promise that bulk buys will lower parts prices, but firm data lag rosy forecasts.

Sustainment costs already outstrip earlier plans. Depot lines encounter longer turnaround times because they must wait for engineering instructions tied to unverified fixes. Spare-part shipping gets slower when vendor quality escapes catch faulty batches. The broader logistics system remains fragile, and ALIS drives much of the problem space. Until ALIS stabilizes, readiness rates oscillate across wings.

Congressional auditors outline worst-case budget exposure. An April GAO brief cites still-rising sustainment dollars and warns that planned cost reductions remain aspirational. Staffers hint that future aircraft ceilings could force services to cut buy quantities if lifecycle bills fail to drop.

In the near term, flight lines focus on day-to-day performance. The Air Force training wing at Luke AFB reported multiple oxygen-system incidents last year. After investigation, tech reps installed new flow sensors and changed cockpit-pressurization logic. Incidents dipped but did not vanish. Test boards monitor data hourly, ready to ground flights again if spikes occur.

Amid those technical skirmishes, the F-35 still flies real-world missions. Israeli jets conducted strikes in Syria, according to press leaks. U.S. Air Force F-35As deployed to Europe and the Pacific on theater-security packages, collecting electronic-order-of-battle data. Every combat sortie feeds software labs with waveforms and threat logs that circulate across the user community.

The balance sheet stays conflicted. Performance grows, but the cost to unlock it keeps climbing. Aviation Week’s comment section distills that paradox: one aircraft wears many crowns – technological marvel, budget buster, tactical edge, and acquisition cautionary tale – often in the same sentence. For now, the argument remains unsettled, just like the modification ledger.

Milestone C Approval and Concurrency Risks Shape F-35 Production Path – MARCH 2025 UPDATE

Eight years have passed, yet the conversation refuses to fade. Supporters point to clear gains. Detractors keep score on delays that still bite.

The headline event arrived on 12 March 2024, when the Defense Department finally signed the Milestone C memo. Full-rate production is now authorized after a five-year slip. Lockheed celebrated, but the ink hid caveats. The decision carried 32 “concurrency risk” waivers that allow jets to roll out while fixes continue.

Technology Refresh 3 sits at the heart of those waivers. TR-3 bundles a new core processor, memory, and panoramic display. Without it, Block 4 capability cannot move from lab rigs into cockpits. Lockheed disclosed in January 2025 that the full upgrade “might not happen this year.” Supplier integration snarled firmware, and electromagnetic-interference tests found unexpected noise on mission-data buses. As a stop-gap, the Joint Program Office capped accepted production at Lot 18 quantities until TR-3 hardware stabilizes.

F-35 Block 4 Development Accelerates with Focus on Advanced Mission Systems

ALIS is gone in name only. The Operational Data Integration Network, or ODIN, was supposed to replace the troubled system across all squadrons by late 2023. Budget papers now show initial fielding pushed to 2025. Containerized micro-services exist, but server racks exceed power margins on older flight lines. Some Marine sites still lean on ALIS version 3.6, patched into hybrid clouds that technicians call “Franken-ALIS.”

Retrofit waves continue. More than 985 F-35s fly today. Roughly 450 need at least one structural or avionics fix discovered after 2017. Depot leaders attack the backlog with extra shifts, yet throughput runs below plan because TR-3 parts queue behind production demands. Air Force Materiel Command warns that depot peaks will stretch into 2028.

Block 4 development, already deep into test benches, picks up pace under a $180 million contract signed in April 2025 to convert four jets into dedicated mission-systems rigs. Those aircraft will probe advanced weapons interfaces and new electronic-attack modes. Program officials pitch the contract as cheap insurance against further schedule compression.

TR-3 F-35 Stealth Upgrade Challenges and Sustained Operational Success

Operational data brighten the other column. The global fleet logged 740,000 flight hours with a mishap rate that compares well to legacy fourth-generation types. Israeli Air Force sources credit the jet’s sensor fusion in raids over Lebanon. U.S. Air Force units in Alaska scored 18-to-1 kill ratios in Red Flag drills last winter, according to exercise controllers.

Sustainment costs, however, stay hot. GAO’s March 2024 report notes that the projected cost per flight hour, even after planned efficiencies, misses the Air Force target by 15 percent. Services did carve out savings on engine removal intervals, but engine unit costs continue to grow as production ramps up, blunting any fiscal gains. Lawmakers now tie a portion of fiscal-2027 procurement funds to hitting readiness thresholds.

Allies remain engaged but selective. Canada finally placed its first order for 14 jets in late 2023 after a long contest, yet inserted escape clauses tied to ODIN performance. Germany joined in 2022 after Russia’s assault on Ukraine, buying 35 F-35As to replace Tornado nuclear-sharing platforms. Berlin now complains that its first lot will ship with provisional software. Norway accepted its final programmed delivery last year, but started a study to weigh Eagle passive-sensor packages as a hedge against Block 4 slippage.

Inside the cockpit, pilots still endorse the aircraft. The new panoramic display – already flying on developmental jets – draws praise for decluttering sensor overlays. A Royal Australian Air Force wing commander says the “big picture view” cuts his time heads-down. Yet he tempers that praise with concern that software revisions land faster than squadrons can train.

The narrative no longer centers on whether the F-35 will enter service; it has. The question now is how fast the fleet can climb out of concurrency’s shadow without bleeding sustainment accounts dry. Aviation Week’s comment threads echo that shift. Writers talk less about cancelation and more about reliability metrics, depot throughput, and software patch cadence. The debate matures, even as frustrations linger.

Lockheed engineers claim that the avionics architecture “has room” for classified capabilities planned beyond Block 4. Skeptical readers ask for proof in test reports, not press quotes. That healthy tension still fuels nightly comment scrolls.

The next inflection point arrives when TR-3 finally locks into production jets. If that moment lands before fiscal year close, Block 4 can push toward OT&E in 2027. Slip again, and cost caps may tighten. Either way, the F-35 remains the world’s largest military-aircraft line, and its web of promises, problems, and possibilities keeps Aviation Week’s inbox full.

REFERENCE SOURCES

- https://bulgarianmilitary.com/2025/04/22/180m-deal-turns-f-35s-into-critical-test-platforms-for-block-4/

- https://militarywatchmagazine.com/article/australia-s-ailing-fifth-generation-fighters-f-35s-in-service-have-so-many-performance-issues-they-may-never-be-fit-for-action

- https://breakingdefense.com/2017/06/breaking-alis-glitch-grounds-marine-f-35bs/

- https://www.defensenews.com/air/2018/09/12/f-35-operational-testing-delayed-until-latest-software-delivers/

- https://breakingdefense.com/2024/03/pentagon-finally-approves-f-35-for-full-rate-production-after-5-year-delay/

- https://www.defenseone.com/business/2025/01/full-f-35-upgrade-package-might-not-happen-year-lockheed-says/402570/

- https://www.defensedaily.com/start-of-f-35-odin-software-fielding-to-squadrons-delayed-until-2025/air-force/